In this section, we will provide some information about the components of language. In linguistics, these are known as:

1. Syntax (grammar, rules about how words combine to form phrases and sentences),

2. Morphology (how words can be broken into smaller parts of meaning),

3. Phonology (the sound system of language).

4. Semantics (meaning of languages),

5. Pragmatics (how language is used)

We’ll consider these five aspects of language in a simple but useful and practical way in order to help you become your own linguist. Each point will give you a better understanding of English, which is regarded as an international language.

Most of the definitions we have here were taken from Merriam-Webster dictionary, a few were from other sources.

Source: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/syntax

[1] Syntax Considerations

Referring to syntax, the Merriam-Webster dictionary gave the following definition:

a: the way in which linguistic elements (such as words) are put together to form constituents. (such as phrases or clauses)

b: the part of grammar dealing with this.

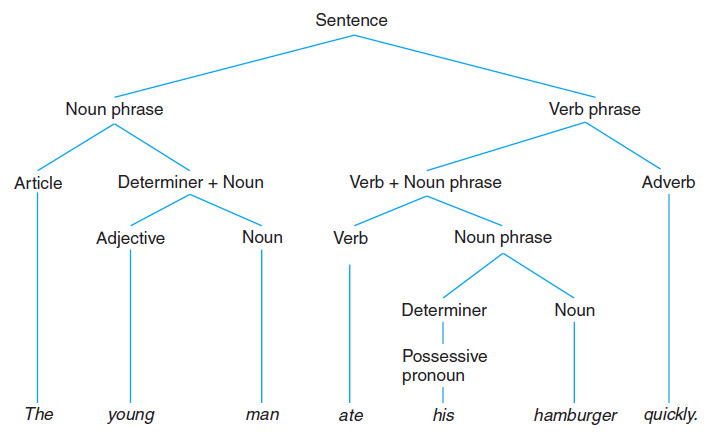

A sample study of syntax, for example, is seen in the “Hierarchical Sentence Structure” below:

Source: Robert Owens (2012:20)

Syntax can be conceptualized as a complex tree diagram as shown above (presented as the Hierarchical Sentence Structure by Robert E. Owens, Jr. in his book entitled “Language Development: An Introduction” published in 2012 by Pearson), but can also be presented in a simple way. Consider the following example:

Article | Quality | Size | Age | Type | Noun | Modifying Phrase |

a | picturesque | little | old |

| town | In the mountains |

an | exciting | gigantic |

| port | city | With lots of street life |

Please Note: When two or more adjectives occur in a sentence, they usually follow this order.

The connection of ideas at the sentence level, also known as ‘cohesion,’ deserves high consideration in the sphere of syntax, this connection affects the tone of your writing. Talking about writing, also click here for the so-called ‘coherence,’ which is the connection of ideas at the idea level that often goes hand-in-hand with ‘cohesion’ in both language and communications studies.

Check the following links for some important documents on coherence and cohesion.

Check the following link for some basic grammar rules regarding “Times and the Appropriate Tenses.”

[2] Morphology

In linguistics, morphology is the form and structure of words in a language, especially the consistent patterns of inflection, combination, derivation and change, etc., that may be observed and classified. It analyzes the structure of words and parts of words, such as stems, root words, prefixes, and suffixes.

For example, the word “polyglots,” the name of our organization can be broken down like this:

Morphology

Elements

Meaning

Prefix

poly-

more than one; many or much

Stem (Inflectional root)

-glot

a combining form with the meanings “having a tongue,” “speaking, writing, or written in a language” of the kind or number specified by the initial element (which is the prefix, if there is any).

Root words

polyglot

able to speak or write several languages; multilingual.

Inflectional suffix

-s

plural mark, meaning more than one

Adding a second prefix will produce the term hyperpolyglot, which was coined by linguist Richard Hudson in 2008 to describe an individual who speaks dozens of languages.

[3] Phonological Considerations

Phonology is the branch of linguistics concerned with sound systems or patterns and their meanings, both within and across languages (including or excluding phonetics).

Formerly known as phonemics or phonematics, phonology was traditionally focused on the study of the systems of phonemes within particular languages. Today, however, it also covers linguistic analysis both at a level beneath the word (including syllables, onset and rime, articulatory gestures, articulatory features, mora, etc.) and at all levels of language where sound is considered to be structured for conveying linguistic meaning.

In written form, linguistic meaning can be easily deciphered by proper use of grammatical structure, punctuation etc., but in spoken discourse, we substitute these for intonation, sentence stress and phonemes to produce ambiguity-free meaning and avoid vagueness. In the utterance, “Let’s eat Grandma,” for example, if the stress is put on “eat,” an invitation is given to grandma for a meal; if the stress is on “grandma,” grandma’s life would be in danger because the speaker takes grandma as a meal.

In English, we do not have phonemic tone, although we use intonation for such functions as emphasis and attitude. That emphasis is seen in the phrase like “do sit down” when someone initially refuses to do so.

Phonemic tones are found in languages such as Mandarin, in which a given syllable can have five different tonal pronunciations.

Chinese Character | 妈 | 麻 | 马 | 骂 | 吗 |

Chinese Pinyin (pronunciation) With tones | mā | má | mǎ | mà | ma |

Meaning | mother | hemp | horse | scold | interrogative particle |

As presented in the table above with the example of “ma,” there are four basic tones in Chinese pronunciation: the high and level tone (1st tone), the rising tone (2nd tone), the falling-rising tone (3rd tone), and the falling tone (4th tone). There is also a neutral tone (sometimes referred to as the fifth tone) which is intoned only very slightly. The tone of "phonemes" in such languages are sometimes called tonemes.

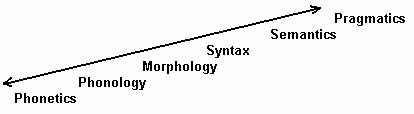

As SIL noted, phonology is related to many aspects of language such as phonetics, morphology, syntax, and pragmatics. Here is an illustration that shows the place of phonology in an interacting hierarchy of levels in linguistics:

Source: SIL Glossary of Linguistic Terms http://www.glossary.sil.org/term/phonology

In phonology, the phenomena of assimilation, and relaxed pronunciations (informal contractions) are worth considering. We’ll start with relaxed pronunciations, some common English examples are given in the table below.

Relaxed Pronunciations | Conventional Structure | Examples |

Ain’t | 1. am not; are not; is not 2. have not; has not | I ain’t a fool Her husband left and she ain't never been the same. |

Gonna | going to (+main verb) | What are you gonna do? |

Wanna | 1. want to (+main verb) 2. want a (+noun) | I wanna get out of here You wanna slice of pie? |

Gotta | 1. have got to (+main verb)/ 2. have got a (+ noun) | I gotta go now/ John, you gotta minute to talk? |

Gimme | give me | Oh, gimme a break! |

Lemme | let me (+ main verb) | Lemme tell you this… |

Kinda | Kind of | You kinda look like my best friend. |

English is spoken in many ways around the world, but the two most well-known varieties are the American and British styles. The English language examples used in these articles come from these two varieties of English.

[4] Semantics Considerations

“Semantic features,” remarked Robert Owens (2012) “are aspects of the meaning that characterize the word. For example, the semantic features of mother include parent and female,” he explained. A key concern of semantics is how meaning attaches to larger chunks of text composed of smaller units of meaning. Generally, semantics includes the study of sense and denotative references, truth conditions, argument structure, thematic roles, discourse analysis, and the linkage of all of these to syntax. It is also closely linked to the subject of representation and other disciplines. When analyzing language, the “architecture of meaning” can help us more clearly understand our semantic focus.

The Architecture of Meaning

Lexical

Semantics

1. Morpheme Meaning

2. Word Meaning

Compositional

Semantics

3. Phrasal Meaning

4. Sentence Meaning

Pragmatics

5. Utterance Meaning

By focusing on compositional semantics, here we’ll try to help you overcome the language confusion, (language interference) known as “Chinglish” in China. We can define Chinglish as the kind of mistakes commonly made by a speaker whose first language (or L1) is Chinese, when speaking English as their second language (or L2.) For example: If you, as a non-native speaker of English, were to hear the phrase “you have the green light” meaning “you have the permission to proceed” without any other context, you might misunderstand the phrase’s meaning in one of the following ways (all of which could be true, following conventional logic):

“you no longer have to wait to continue driving,”

“the space that belongs to you has green lighting,”

“your body is cast in a greenish glow,”

“you possess a light bulb that is tinted green,”

etc.

[5] Pragmatics Considerations

You want to be clear and precise in order to be an effective communicator. In this section we will give you some examples of language being used in different contexts, with the goal of helping you eliminate language ambiguity. According to Robert Owens (2012), pragmatics consists of the following three aspects, the first two of which we will explain below.

■ Communication intentions and recognized ways of carrying them out.

■ Conversational principles or rules.

■ Types of discourse, such as narratives and jokes, and their construction.

A. Communication Intentions

In order to be valid, said Owens (2012), speech must involve the appropriate persons and circumstances, be complete and correctly executed by all participants, and contain the appropriate intentions of all participants. “May I have a donut, please” is valid only when speaking to a person who can actually get you a donut in a place where they are available.

B. Conversational Rules

When changing a topic of a conversation a speaker needs to use an expression such as “by the way,” as in:

A: Are you hungry?

B: Yes, I am.

A: By the way, how is your mother Maria?

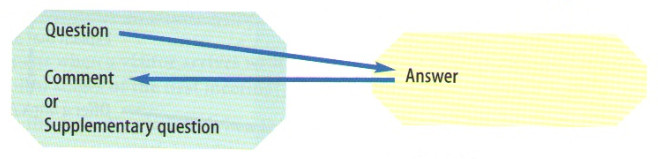

Without this transitional phrase, “A” might break the flow of conversation, or risk being misunderstood. In order to eliminate the possibility for confusion and keep the conversations flowing smoothly, one can follow the following principle as seen in Sweeney’s Communicating in Business published in 2003 by the Cambridge University Press:

Source: Simon Sweeney (2003:06)

Generally, if you ask a question you should comment on the answer or ask a supplementary question or, at least, use some ‘backchanneling’ techniques, e.g. “uh-huh,” “I see.” The answer given by the Manager in the following instance, for example, breaks the “rule” of conversation:

Situation

Randy Hall from the U.S. is visiting a customer in China. He is talking to the Production Manager of a manufacturing plant in Wuhan.

Conversation

Manager: Is this your first visit here?

Hall: No, in fact the first time I came was for a trade fair. We began our operations here at the 2015 Exhibition.

Manager: Shall we have a look around the plant before lunch?

Correction

The manager could improve the flow of conversation by following the above rule, at least acknowledging Hall’s response, or better, responding to it before moving on.

Conversation

Manager: Is this your first visit here?

Hall: No, in fact the first time I came was for a trade fair. We began our operations here at the 2015 Exhibition.

Manager: I see. How do you feel things have changed here since your first visit?

C. Semantics Vs. Pragmatics

Semantics and pragmatics may be difficult to distinguish for those who do not study linguistics extensively. Let us look at the difference between the two in a simple and understandable way:

Semantics vs. pragmatics

Semantics: Literal/conventionalized meaning

“Core meaning,” independent of context

This belongs to semantics proper

Pragmatics: Speaker meaning & context

What a speaker means when they say something, over and above the literal meaning.

This and other “contextual” effects belong to pragmatics

_____

Source: https://www.um.edu.mt/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/137111/Week_1_Lecture.pdf

Aim far with thoughts, acts an’ words

|  |

| Website |

GPN (Global Polyglots Net.)

GPN Education Consulting (Wuhan) Co. Ltd.

Office: Wuhan Jiang Xia Cang Long Dao, Heng Ji Industrial Park,

Building 2, Apartment 802, Wuhan, Hubei P.R. China

中国湖北省武汉市江夏区藏龙岛恒瑞创智天地2号楼802室

Phone: +86 (0) 27-87219719| Mobile: +86 13036101322

Email: info@gpn.services | Website: www.gpn.services

GPN, The Company You Can Trust

2017 © GPN Language Services & Consulting, All Right Reserved